Looking For Lois

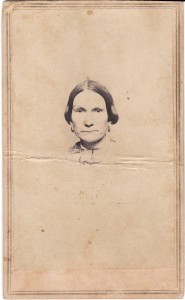

My great, great, great grand mother Lois Grant Holman, 1813-1856 This faded daguerreotype, most likely taken in the 1850’s is the only known image of her.

“Strange, isn’t it? Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he? “It’s a Wonderful Life”, 1946

“For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.” Virginia Woolf

Introduction

Her ancestors and relatives included a Mayflower passenger, a Governor of Connecticut, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a United States President. Three of her male descendants founded multi- national corporations. I found it easy to access information about the men that make up the the family tree of my great, great, great grandmother Lois Bulkely Grant Holman. Yet, like many women of her day, little seemed to be known about this woman who packed up with her husband and three children and came west to the bluffs of the Missouri River in Iowa from a comfortable life in Connecticut, in the spring of 1856.

The faded picture of her I finally ran across online, shows an eerie image of simply a face, rather plain, and looking somewhat sad and severe. A whole part of her is missing, like her story.

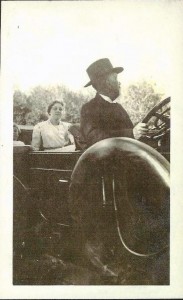

In adulthood, all I remembered about her from childhood stories told to me was that she was an early pioneer in our little part of the world, she was related to Ulysses Simpson Grant, and she was our connection to the “Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution”. More recently, though I’d recorded this years ago, I looked again at her death date , July 2 (in some records July 3), 1856. My date of birth is July 3, 1956. My favorite great grandfather, Holman Waitt, Lois’s grandson that she never knew, was also somewhat connected to this, being born July 2, 1886. Lois was also referred to in records as “Louisa” or “Louise”, my middle name, something my relatives never said to me, and most likely didn’t know.

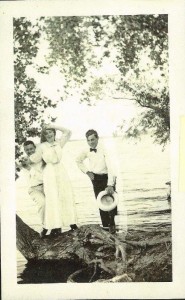

With my great grandfather, Holman Waitt, Lois’s grandson, in the late 1950’s. He told stories of our history.

There was a symmetry to all of that and I decided to start digging. Stumbling across her rather interesting male antecedents was easy. But I wanted more. What I found was a piece of the story about the woman who made my existence possible. It came from her own hand, a letter written April 27th, 1856 from Sergeant Bluff, a small town south of Sioux City, named for 22 year old Kentucky native Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only man to die on the Lewis and Clark Exhibition. The location of the original letter is still to be determined and I have yet to track it down, but copies can be found in two or three museums. My first copy was given to me several years ago by Sioux City Museum curator Grace Linden. I would imagine its value for others lies in a rarely told story of pioneer life so early in this area, from the woman’s point of view. For me, it’s a priceless piece of my own family history, a history that is heavy with stories of men, but light on the stories of the women. That she died not two months after the letter was written made me want to know more.

Pilgrims, Pioneers, and Presidents

Lois Bulkely Grant was born in Rockville, Connecticut 200 years ago, on April 14th, 1813, to a family that was present and part of most of the key events in American history. As her fifth cousin, Civil War General and 18th President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant stated in his memoirs, “My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral.” Her fifth cousin was right.

Her mother, Electa Fuller was a direct descendant of Mayflower passenger Edward Fuller, a signer of the Mayflower Compact and his wife, Ann, who died the first winter of their arrival in the New World. Her father, Elisha Grant was the descendant of the immigrant, Matthew Grant, a co-founder of Windsor, Connecticut, who arrived at the colony of Massachusetts Bay on the “Mary and John” in 1630. Elisha also counted as his ancestors on his mother Lorana Strong Grant’s side a Governor of Connecticut, Roger Wolcott, and Oliver Wolcott, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The town of Rockville, where she grew up as Elisha and Electa’s fourth and youngest child, was founded by her great grandfather. Samuel Grant in 1726. By the time of Lois’s birth, the town was populated with the descendants of the children of her grandfather, Lexington Alarm minuteman and Revolutionary War veteran Ozias Grant, and her grandmother Lorana Strong, who gave birth to an astonishing 14 children. Elisha was the 10th of these children and is described as a builder and carpenter. Electa is described only by her family tree and her death, at 37, when Lois was four years old. The Grants, were part of the fabric of the little town, as owners of the woolen mill, landowners, soldiers, farmers, and deacons of the church. Her uncle Elnathan is described as the last survivor of the Revolutionary War in Tolland County.

Marriage and Family

There is no further information on Lois until she married my great, great, great grandfather, William Palmer Holman in 1837. Palmer, as she later calls him in her letter, from an old Connecticut family, apparently moved with his father to Salisbury, Vermont where he was in the business of manufacturing shoes for ten years, then returned to Connecticut, where their five children were born. Records generally show three children, but a further search told me that two of her five children did not survive childhood, not an uncommon occurrence in those days. Lois became the mother of Charles Jerome, born 1840; Albert Murillo, born 1845, Daniel born in 1848 and died young, Ella, born 1851 and one other child who died who also died young, referred to by her son Albert, but never by name. What possessed this family to leave their familiar and most likely fairly comfortable roots in the East and head to the wilderness of western Iowa is not known.

Going west

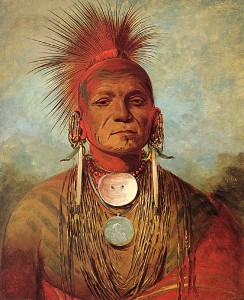

What is known is that Palmer came first, in 1855, traveling by rail to Illinois, to Independence, Iowa by stage coach, and to northwest Iowa with horse and wagon. A man named Bronson, a carpenter, accompanied him. The few settlers there, in what was called Sergeant Bluff City, seven miles south of the newly formed Sioux City, offered to build Holman a hotel and give him land, if he would return and manage it. The 1891 book “History of the counties of Woodbury and Plymouth, Iowa” recalled, “During the years 1854 and 1855 came William P. Holman, Leonard Bates, Gibson Bates, T. Ellwood Clark, William H. James, and a few others.”

When Palmer made the decision to return, Bronson remained there and built the small hotel and Palmer went back to Connecticut to “sell out”, as it was stated, and to bring along Lois and the three children. I like to think that a family conference was held, as it might be now between husband and wife, but my guess is that it being 1856, there was not much talk, and it was “whither thou goest, I shall go.”, and go she did.

Her son Albert, who later became a journalist and writer tells the story of their journey in his 1924 book, “Pioneering in the Northwest” :

“Mr. Holman sold out in Connecticut, and early in February, 1856, started shipping goods (and the other four Holmans) by rail to Iowa City, just completed. It took the train a whole afternoon to go from (Davenport to Iowa City) that 50 miles. The Holman Boys, when they got tired of riding, would jump off the train and run along behind the engine. Mr. Holman had bought a wagon and a team of horses in Chicago and shipped them to Iowa City. He bought four yoke of oxen in Iowa City, and they started for Sergeant Bluff. Three hired men and their three children and one adopted daughter made up the party. The children were C.J. Holman, aged sixteen, A. M. Holman, aged eleven, and their daughter Ella, aged six. The journey consumed 23 days. It took nine days to get from Council Bluffs to Sioux City”.

At the Little Sioux River, the rope ferry washed out and they joined forces with Charles Larpenteur, who kept the ferry…They cut dry cottonwood logs, made a raft, and with a new rope managed to get ferried over. W.P. Holman drew up to the hotel in Sergeant Bluff in April of 1856. The building was 18×24 feet, fourteen feet high, a story and a half. It was crudely built of cottonwood lumber sawed from th nearby woods, boarded up and down with cracks battened with strips, and shingled with long thick shingles…The second floor was reached by a ladder, and this floor was called “Texas” by the Holman boys. The boys beds were here and also a place for “guests” who were only men. It seems their idea of a hotel consisted of a ladder and a floor. He continues, “The first winter the snow had to be swept from beds before the guests and the boys could sleep.”

I try to imagine a woman later described by her granddaughter, who never knew her, as a “woman of gentle birth and delicate physique”, enduring this trip, this 18 x 24 foot “hotel” as a home, far from her roots. The letter provides some clues. This typed version, done in 1940 and just given to me recently by the Sergeant Bluff museum gave me a little more information about her death and solved the mystery of where the original letter was kept for many years. It was a home I visited many times, the home of my great grandparents. I may have seen it myself. This version of the letter reflects the original story told in the Sioux City Journal May 14, 1929.Some of the grammar and sentence structure had been modernized in this version, and the original they were working from was difficult to read.

The letter, written two months before her death:

Sergeant Bluff City, April 27

Dear Mother, Brother, and Sister,

As I have just received a letter from you with the greatest pleasure I thought I would answer it. I began to think you had forgotten us, but I know it takes a great while for a letter to go through. I wrote a letter to Alden’s (brother in law) father since I got here so I shall not write the particulars of our journey out here.

We are all well and keeping house after a fashion, but have not as yet very much to do with. Palmer has been down to the bluffs after one load. We have a bedstead and seven chairs and a good big stove. You would laugh to come in and see how we live. The boys have to sleep on the floor. We have no pantry or cupboard and we have to use trunks for a pantry.

We are going to have more room as soon as they can get up a log kitchen, bedroom, and pantry. We have a joiner working here now. He shingled the house we live in this last week. After he got the board roof off to commence to shingle, it began to rain and such a time we had you never did see. It made me homesick you had better believe.

We have a log barn built and the stages have begun to stop here. They go up to Sioux City one day and down the next, and when they come, they take breakfast here. There is a good deal of travel by here and we could have the house full every night but have no way to accommodate them yet. The place is building up faster over in Nebraska than it is here, and it is said it’s the handsomest country by far. Palmer went over last week and secured his claim. He can get a thousand dollars for it but he will not sell. They say the grass is almost big enough to mow over there.

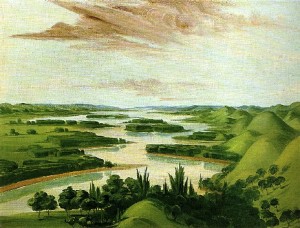

Our boys commenced plowing last Monday with three teams. They plowed around a small garden patch of a hundred and sixty acres the first day! It is two miles from home. They have built a small shanty down there and will have to stay down there all the time while the weather is pleasant until after planting. They will have great times, I expect. It is a great country out here and is very pleasant. I wish you could be here and go up on the bluffs. They are close by here. Lucy (adopted daughter?) and I went up one day and it made my head swim. We could look over to Nebraska and see for miles around us the prairie as level as the house floor.

Jerome (son) has just got home. He has been forty miles after some of our goods and to get some potatoes and meat. He has been gone five days. He saw a snake curled up by the side of the road and jumped out and stepped on the head. The snake began to rattle his tail but Jerome killed it and brought the rattles home. It had four. I scolded him, but he said it was no different to kill a rattle snake than any other. We have not seen more than two or three deers, but there are wild geese by the hundreds. And ducks worlds of them but there is none here now.

We have meetings here once a fortnight. One sermon is preached in a store by a Methodist minister who is quite a learned man. He called on us yesterday and took tea with us. All the ladies that live here have called on me, the whole of six. I have not returned the calls but must begin soon or I won’t get around this summer. There are plenty of men here, however. They cast sheep’s eyes at Lib and Lucy’s girl but none has popped the question yet. I expect to hear any time that they have though.

The children are all contented but Ella says when she goes down to see Grandma, she shall stay there. She goes on a double trot over to Lucy’s which is close by and back again. As for myself, I like it here just about as I thought it would. If I had the same conveniences that I had back east and my friends were all here I could be contented, but I have some melancholy hours and a few crying spells does me some good.

I think of you and want to see you all, but when i think of the distance between us my heart sinks within me. Gardner, (half brother), I wish you could come out here and see the country and some of the rest of our friends. Give my love to all and receive a share yourself. I will leave the rest for Albert. Palmer wants you to send a paper once in a while. He will write the next time. Write again soon and write all the news you can think of.

Your affectionate daughter and sister, L. Holman

Following are postscripts from her sons, 11 year old Albert and 16 year old Charles Jerome,

Dear Grandmother, Uncle, and Aunt,

As mother has been writing to you, I thought I would write a few lines too. I can’t find much to write but I will try to see what I can do. I like the country first rate. I have been up to Sioux City once and when I went, Jerome and I and another man went up to Floyd’s grave. He has been buried there 52 years. I have to drive a team this week. We have five yoke of oxen where we are plowing. It is about four miles down there. We have built a log house and we will stay there while we work the field. Mother has to get supper and I have to get out of the way, so goodby, from Albert Holman

Dear grandmother,

As mother has written you I will put in a few lines. Mother has written most of the news. I like the country very well. It looks about as I thought it did. I have just got home from down the river and am going to start back for Council Bluffs (90 miles) tomorrow which will take me about 10 days. Give my love to Alden and Statira (uncle and aunt) and tell them that I will write when I get back. I killed a rattle snake today. I will send the rattles to you. (This young man is determined to have somone see these rattles).

Two sources helped me close the gap between the April 27th letter and her death July 2nd. The 1929 Journal story states that according to her sons, even at the time she wrote, “she knew that she was the victim of a dread malady and that her chances of recovery were very small. She kept her secret until failing strength gave it away. The father in desperation sent an appeal to General Harney, who was in a camp across the Big Sioux, and Mr. Holman thought there would be a good surgeon with the troops…In spite of all that could be done, however, in less than two months after the letter was written, Lois Holman died.”This brief description by her grand daughter Abigail in 1933 on the death of her own father, Albert, She says, in part…“ The hard trip and lack of comforts proved too severe for the mother, a woman of gentle birth and delicate physique. She lived only a few months after their arrival on the frontier. Mr. Holman had sent to Ft. Randall in South Dakota for the army doctor to assist Dr. William Smith of Sioux City. Lois Butler Grant Holman was buried in the hills east of the town of Sergeant Bluff in July, 1856, one of the first burials among the settlers in this vast and lonely region. Later her remains were removed to the present Sergeant Bluffs cemetery, which her husband was instrumental in having established as a township cemetery.” What the “dread malady” was I may never know.

What came after

William Palmer Holman remarried Caroline Mattison of Wisconsin sometime in 1857. She was described as kindly and refined, and gave birth to two more Holman sons, Milton Palmer and Edward Henry. She was also listed as the first school teacher in the area. Palmer continued to farm, raise cattle and founded WM Holman and Sons. Charles Jerome joined his father in farming and in the brick business then called W.P. Holman and sons. Albert, became a journalist and writer and eventually joined the family business as well.

Charles Jerome, referred to as CJ. married Meda Euseba Cole, who died young and had one child. He and his second wife, Kittie Carpenter had five children. He died in 1925, at 85. Albert married Emma Eliza Webster and died at 88 in 1933. They had five daughters and a son.

Both of Lois’s sons were present at the reburial of Lewis and Clark’s Sergeant Charles Floyd, a grave they had seen as children more than 40 years before this photo was taken.

Lois’s youngest child, little Ella who would have rather stayed in Connecticut, stayed in Iowa and married my great, great, great Grandfather, Sioux City Stockyards pioneer George W. Waitt. Ella. a tiny woman like her mother, gave birth to 11 children, including my beloved great grandfather, Holman.

Ella Holman Waitt, her husband George W. Waitt, her children and some grandchildren, Sioux City, Iowa 1925. My great grandparents Holman and Hazel Waitt are back row, third and fourth from left. My grandfather Theodore Waitt was is back row far right.

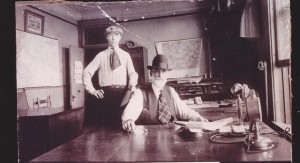

Lois’s grandson Bert Waitt and son in law George W. Waitt, Sioux City Stockyards office, date unknown.

The descendants of the 22 grandchildren of Lois B. Grant Holman are spread far and wide across the country, as is my branch of the family, after being here for six generations. Only a few of us remain in the area, but the ties are still strong.

I visited Lois one cold day two months ago in a cemetery once called “The Holman Cemetery” south of town. She is on one side of her husband, William Palmer. On the other, his second wife Caroline.

To the side of this, though, her original grave stone from 1856. Like Sergeant Floyd, she was moved to a re-burial site late in the 19th century. His sandstone obelisk monument stands 100 feet tall and greets visitors to this northwest Iowa river city. You can’t miss it on the way in. Lois’ monument is tucked away in the Loess Hills, small and barely readable. I’ll be going back this spring, to take flowers, and to thank her for all she did for all of us.

With gratitude to Grace Linden and Steve Hansen of the Sioux City Museum, to the family of Grant Holman and to Jerry Logemann and the Sergeant Bluff museum.

Comments (4)